I first got the opportunity to meet Nasan when his work Backpacks were shown as part of the touring exhibition Future Perfect

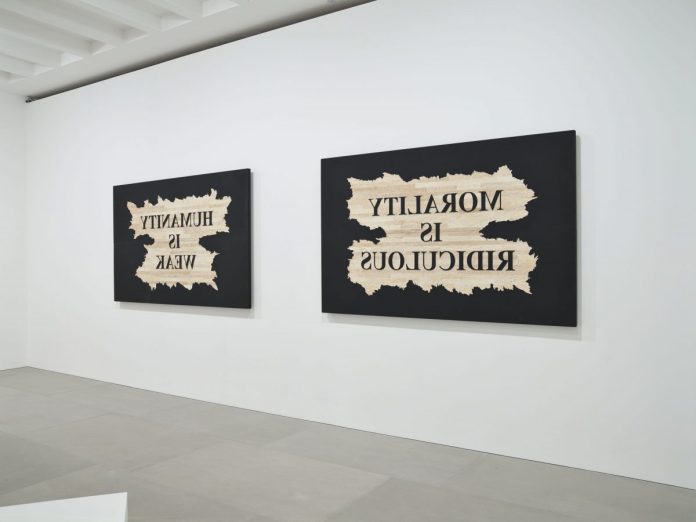

Nasan Tur With Woodcut (Empathy is Naive) (2015)

in The Model earlier this year. In preparation for his arrival, I studied his practice intensely, and I found that he put great thought and depth to his work, and I was so glad that he agreed to do this interview as I am excited to share his process.

Let’s start with Your works Backpacks and where they came from?

Most of my works are related to each other in one way or another, and well the backpacks, they came from a work called What I always wanted to tell you. And it’s a work that you can only really present when an institute has a connection to a busy public space, like a balcony or a huge window. It has to be frequented often, and you have to be able to see the public from the balcony – so not a like a back yard! So, the work consisted of a microphone on a tripod, that was connected to two huge speakers that are turned on. The exhibition space includes access to the balcony or the window where the tripod would be, and when you make one step towards the mic, everything that you are saying into the microphone is broadcast to the public – very loudly. So a lot of people can hear you, and it makes you much more present to the public. Louder than other people. You stand higher than other people.

I’ve shown it in a few different places – I made it in Berlin last year, and I made it a couple of years ago in another city called Wiesbaden in Germany. Istanbul as well, and of course it always has to do with the circumstances in a place like Istanbul. It feels like it is much more dangerous to do it there, as you can get jail for expressing criticism (especially when you do it publicly). In Germany, where you should be safe to say anything in public, the usage is different and that is the work.

What I always wanted to tell you (2007)

In this way, it’s not so much about what the public use the microphone for. For me, it’s more about which kind of context, circumstance, and how the people accept it as a tool for their use. I think we did it in Turkey at a time where it was possible to do it. (Granted, even then the police came and shut down the exhibition for a day, but the very next day we were able to open it again.) Today it wouldn’t be possible – it’s too dangerous because of the nature of the project, because you lose control out of it and leave it to the public. It is about free speech and the democratic way… that means also that people can be given a platform for free speech, and say things you might not agree with, and you are not in control of that. Looking at that freedom, how far can someone who claims freedom for art also accept that? And accept these different opinions?

Backpacks (2006)

So the backpacks that came later, they followed on this idea of a place where I create a platform – which can be used, but doesn’t have to be used. It’s more about the thought: ‘do I want to have this position over others? do I want to be louder than others?’ And: ‘do I have to say something to people? Do I have the courage to say it?’ So, all these questions play a lot with the idea of… the question I have is, like, when are you actually active? When you stand in your position in public. It was after exploring this idea when I made the backpacks, as I liked the idea I that I wanted to expand the borders of the gallery, or the institution or the museum. I wanted to create objects which are in the art context – they exist as an art piece, but when you take it out from there, it’s just a functional tool. So it’s about making art pieces that are usable, functional, and that create a platform to ask: what you would use it for?

It’s interesting how your work takes on a functional quality to them, like the woodcuts in Funktionieren.

Woodcuts (2015)

A woodcut is a work that’s actually a tool, it’s not only a picture or a text, but an object that can be used. People can hang it on the wall, but you can also can take it from the wall and use it as a wood block, like a printing block for wood cuts. It’s an artwork which can reproduce itself in an unlimited way.

That’s the reason I chose woodcuts – it is one of the oldest reproduction techniques known to man today. I think of the invention of woodcuts, where people were able to reproduce many of the same picture or writing for more people, and this parallels today with social media. At the moment with social media, we can provide people with information very very easily, with copy and paste, and Facebook and Twitter – it is a turning point, like the woodcuts were in their time. Nowadays social media is taking over the old media like the newspapers and television, and this has changed how we digest news; there is no time anymore, to rethink what we are reading or to question what we are reading. So, it’s a kind of perception that we have kind of just got used to – very very fast, and very very easy. Easy in way where they pretend to answer very complex questions with very easy answers. So, I tried with these artworks (the woodcuts) to question this, by taking these phrases which I took more or less from social media with these phrases, statements which are very absolute (highly black or white). Statements about very controversial issues, where you are either really for it or you’re totally against it. But that is not so easy – to say I’m totally for it, or I’m totally against it. And the length you spend with something – that also relates to the woodcuts, the reproduction process. Which is such a long and drawn out process, it’s prolonging the time it takes to digest the information – to allow you to question the way that you go through the world, the way you get your information.

It’s also like the whole thing is a confrontation with media at the moment. Yeah, you have two hundred or two thousand television channels! If you don’t like one, in two seconds you make the decision. You don’t give time to anything anymore, and that makes us also very… how do you say? Very ‘influenceable’. So people from the outside… even if you don’t know they influence you, they do. It’s not just about the fastness, it’s also like, who is giving you the information that you are going to use to build your opinion? It always depends on the angles. So for sure, people in Russia will get totally different information from their news about the Ukraine/ Crimea situation compared to the information we are going to get. So, what does it mean to influence people? We are not aware about that, we just take it at face value and just swallow it.

I think art can be a language which can give us an alternative perception. To be aware again about these things. So, I try to demand things from the visitors in my shows or the visitors of my artworks. Usually they don’t function in two seconds like a traditional oil painting might. I get really pissed off with these things, because what does it mean? You know, to give something like two seconds? What does it mean to read the number of deaths in a disaster or an act of violence, and in the next second to read another number? Then another number and another number… it’s not like you are getting what’s really happening. It’s getting super abstract, and you’re not even becoming aware of this – how you don’t actually see the thing. It’s not just about having the information, but realising what is behind the information!

You touched on this in the Cloud series.

Clouds (2012)

Yeah, I mean the Cloud series is also evidence of failing on the part of the artist. It’s an artwork with a purpose, the purpose is that you do something politically incorrect here, because this image is only part of what is being photographed – so the real incident, you don’t even get to see it. There are press photographers all over the world who risk their lives, and many who have died or have gotten injured in doing their job… for us, more or less. And what I am doing with the Cloud series is cutting out all this information, the information that the photographers have risked their lives for. Photographs depicting rioting, acts of terror and war, and what I’m doing is just focusing on the sky in that image. So, cutting everything away and leaving only the sky there. So, what does that mean? How can we properly perceive this photography, this wave of photography that we see every day in the news? Because I can see myself in that position. I was not able anymore to distinguish abstraction from reality, so what I have done is actually what I have done as a child when everything got too much. I would lie on the field and look to the sky for a short moment maybe for a minute or less, and try and forget my problems with family or girlfriends or school, and that was really a dreaming moment. But that moment was very short, and that is exactly what I have done with that photography piece.

Cloud No.2: 19 May, 2010, Bangkok, Thailand, (2012)

So at first glance people see this beautiful photography, something romantic, something vast, but actually, they aren’t really clouds… When you look closer, the clouds are mixed with ashes and smoke, and also the way they are photographed – you also feel that there is something wrong. This is not just a romantic photograph, there is something behind it, and by exploring the whole photographic series, you realise something is going on. I have these tools I use – beauty or romanticism – often to draw the viewer in to the work, but you have to peel away the artwork by spending time with it, to see that there are more layers to it. To get to the core. And that is not so easy, and it is not so easy for me to deal with in the work. But saying that, I feel that art shouldn’t be easy for the viewer, art should demand something. Disturb something! And, make something more than just a good feeling. That’s how I do the work I do.

Let’s talk a bit about your background – how you got into art?

I don’t have what you might call a classic background in art. I never drew when I was a kid, and I didn’t have art on my mind all that much as a child. I’m not that kind of person. The first time I was in a museum I was 18! For me it was more or less an accident that I became an artist, but still it’s something that I feel that I have to do. Like, if you see how the world is going, you have to think also about your role in this society, and that is what I’m doing – I have this feeling, that I can find a role for myself through my art. And the topics that I’m dealing with, I feel they are important.

There are some strong transmorphic elements to your work. I really like that piece of the shattered diamond [Diamonds, 2018] you did recently.

Yes, it’s a new series that I am working on at the moment, where I am crushing real diamonds in a violent act. And because of their material consistency, they don’t break normally – rather, they explode and what you see actually is the result of this explosion. You see many many fragments of the diamonds – from one diamond, many many hundreds and thousands of small diamonds are created that are all different sizes. They don’t have the same value anymore, at least from our usual perspective – it’s more about changing from one form to another variation. And it is not only about the beauty of the diamond, they’re charged with symbolism – with desire, technology (as in how it’s used to cut things which other material can’t). They are the hardest material in the whole world. And actually, when attempting to break it, in the end it created something new, and became something so beautiful. I liked this metaphor behind the picture a lot.

Diamonds – 1,00ct (2018)

But of course diamonds have other levels of symbolism in our society – we often see that beauty and forget everything that’s behind it. So, what does it mean actually, to see a blood diamond on the ring of a rich man or woman? That natural diamond had to have been found somewhere. So we forget about all this slavery of people in Africa and South Africa, and the people who die for this working in the worst conditions, and that doesn’t concern us because we want this shiny thing… this kind of background of wealth and power with diamonds, I just wanted to break and destroy it. And by breaking it out of that, I created something that is really valued, which is variation. Every splinter is something different in that field. That art market aspect of this is also interesting; you destroy something valuable, and the art makes it even more valuable than it would have been before you destroyed it! So in that context, I also find it valuable.

Tell me some more about your project, Variationen von Kapital.

Variationen von Kapital. (2013)

Kapital is an ongoing work. I’m interested in what the word Kapital actually means today. Economics plays a huge role in the art world today, and from my perspective, it’s not healthy for art. The perception of art that the public has – it’s not the content of an exhibition you are going to read in the newspapers nowadays, it’s almost always going to be of a new record sale. it’s all about maximising the capital out of something and so art is an investment. So, I wanted to create an artwork that deals with these questions of capital, capital inside of art, the desire of art, the role of art, the function of art. But also about human capital, capital work, what uniqueness we can find in this.

Variationen von Kapital (2013-ongoing)

For the work I created versions of Kapital, or variations… firstly I worked with a computer technician to write a formula for me, so the computer spits out all the versions all the word Kapital in the German language, that I could transcribe. So I write the word so you can still read it phonetically, but you never actually have the right spelling – you always have different punctuations, like with two AA’s or IH, but always reads Kapital. There are more than 41,000 variations to work from, and then the computer gave me all these variations in a random order for me to transcribe them. So the computer told me what to write! I wrote them down on handmade paper with Indian ink, each of them on a one to one, I signed and dated it, so it became a unique drawing. But this drawing exists in more than 41,000 variations. It takes a while! I only made 800 for that exhibition, but to make the whole 41,000 to finish this artwork, I would need more than ten years. Every day, twelve hours to do it. It’s more like contract work, there are ‘clauses’, and they’re part of the work. For instance, I’m not allowed to choose which one I would like to produce as an artwork. The computer tells me randomly, and I must draw the variation it gives me, so the artist is a tool inside of that project. And then the price of each piece is also fixed at €1,000 each, the gallery is not allowed to make it higher and they’re not allowed to make a reduction to the price either. And then the buyer is allocated one randomly. The artist produced it in a random way, so the collectors also choose one in a random way! So, it plays itself against the usual ways of the art investment market, it goes against the usual conditions. So, if you have one it is a unique piece, but it looks like an edition of 41,000. What kind of value is it, still? It is a question about investment, and uniqueness, and the way you can actually choose an artwork. The work goes beyond the written capital.

You can find out more about Nasan’s work through his website link below