Anishta Chooramun

This interview was recorded in October 2019 before the Futures exhibition in the RHA. Anishta Chooramun is a Dublin based artist. Anishta works in the medium of sculpture whose work explores themes of culture, material and identity. These are concepts that many of us will have grappled with at some point in our lives, and Anishta takes that familiarity into interesting directions. This leads to very rewarding experience when you take the time to give yourself over to the work and observe the sculptures.

Your sculpture is interesting in both its construction as well as its structure. Could you talk a little about that?

My core subject is identity as a jigsaw puzzle, and how our everyday life changes us—for example, moving from one place to another, the people we encounter. All these changes shape our identities. It’s not just people who shape us, but also the objects around us. If you compare yourself to somebody who lives in the forest, they probably don’t have a concrete house but a hut. They might have mud clay utensils and a fireplace where they cook. I was thinking about that and considering: the material that I’m going to be using will be things we live in and among, like concrete and wood materials.

Our senses definitely get affected by what is around us. When I moved to Ireland, I actually moved into this place I hadn’t seen before getting the keys. We booked online before moving from Manchester. The living room had this Christmas red wallpaper…when I walked in, I wanted to scream! I could not stand it! The second day in the house, I started to peel it off the wall and then redid the walls. I just could not live with it. Your environment does affect you. It dictates our moods, and behaviours.

Kathakers [Take a Bow I & II]- exhibited as part of Unassembled in the Lab gallery, (2019), Concrete, corrugated paper, copper, 115cm x 80cm x 190cm photo by Jamin Keogh

And Then We Met [Looks like Perspex]- exhibited in The Dock Arts Centre Exhibition, (2018), Glass, square steel rod, corrugated paper, black limestone, linoleum, 194cm x 70cm x 50cm

And Then We Met [Looks like Perspex], detail

I am very tactile. I love combining different textures in my sculptures. The materials I use in my sculptures come from a vast array of mediums. I like to play around with the textures. For example vinyl is shiny, so you might combine that with a matte finish of wood, and then concrete, which has a rough finish that contrasts with both.

So, when you make these sculptures, is playing with material where the ideas come from?

Actually, when I start with planning out a work, I don’t really start with what material I want to use. It’s more what movement. And then after that, I think, “What is going to make this movement possible?”

Some of my most recent work is based on a dance called the Kathak. The Kathak comes from Northern India. It’s a dance that has passed from generation to generation, and its movement is very symbolic/allegorical. Originally performed by travellers, it is used to tell stories. The Kathakars communicate these stories through rhythmic foot movements, hand gestures, facial expressions, and eye work, as a kind of sign language. I incorporate references to these gestures and movements, in these sculptures

Kathak Dance

That’s why I settled on the Kathak, because I wanted to bring some language into my work. This dance is a dying practice that you don’t see very often. Contemporary dance has taken over, which is another reason why I decided to use it, I looked into many other storytelling dances related to language, like the traditional Indonesian dance or the New Zealand haka, but felt kathak is/was right for me.

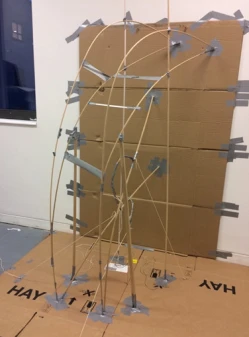

mapping movement

So each movement of the dance is cropped, to create the movements in the sculptures. In one piece, you are seeing her arms go up and go down. The sculptures are, in one aspect, a mapping of that movement. To capture it, I performed the action, and a friend of mine helped me to mark wherever my arms would move. That’s why the end product is not figurative, but gestural. Each movement is like sign language. [Kathakars [Heart Piece]] is so named because, in the dance, she actually touches the ground, and then when she is sitting down, the hands come together at her heart. The dance is a very ancient and traditional dance, from travelling bards in India. They would go from village to village. This dance was a way of telling stories, in a language of its own.

There are a lot of words in Hindi that just can’t be translated into another language. One of these is aahat. Aahat is sort of a presence that is not really there. You might imagine something supernatural, but it’s not. It means a feeling, of someone else’s presence or something has happened. You generally feel an aahat when you are alone. It’s that feeling you get It’s like if somebody has been in your room while you were away. You know somebody has been there, but you can’t tell how, because they haven’t touched anything…that person has left an aahat behind. Think about it: there is no one-word replacement for that meaning in any language.

Between my works, there is aahat, a kind of influence on each work’s personal space. The pieces communicate with each other through their shape, the colour, the size and material. The light that is in the room. It’s all influencing the works. So, every time I show this work in a new space, it may look completely different. The set up would be completely different.

You mention the space between works. Are you thinking about the space where you’ll ultimately be showing the work during your creative process?

I really don’t put that into my thought process when making the work. My focus is to create a puzzle so that the works can communicate with each other. After it is done, then I consider the location. If it’s going close to the door, what piece should be closer to the door? How are people going to receive it? How does it work when shown with other artists’ work? How is it going to communicate with their work?

Kathakers [Heart Piece] exhibited in The Dock Arts Centre Group Exhibition with Patrick Hall and Mary Ronayne, (2019), concrete fabric, white concrete, red vinyl sheet, Glass, Tile, 90cm x 70cm x 55cm

I’m actually changing it a little bit for the Futures exhibition [in the RHA]. It’s no longer going to have a white interior – it’s going to have a red interior. I’m doing some colour testing and also peeling off and adding more texture, so it’s not complete yet.

RHA Futures exhibition series 3, episode 3,

Is it common for you to change works between exhibitions?

It happens every now and then, where I’m not entirely happy with the work. I feel like I need to keep going at it until I’m satisfied. It’s rare to see a painting changing. But sculptures, I think because they’re objects, you have the flexibility to play around a little. The artist might decide when moving it to put it on a plinth or suspend it; all that can change the way the public will engage with the work. But saying that, I don’t really think of how the public will respond to it. I’m not sure if this is a good thing or a bad thing.

The public love certain works. That I feel aren’t fully resolved. I don’t know how people are going to react to changes – whatever those changes end up being – but for me, I have to feel a work is resolved before I can completely leave it.

You mentioned earlier about the works being a puzzle.

I used to do a lot of origami. Folding small pieces of paper and bringing them together to

And Then We Met [Mother Piece]-under construction, (2018), Wood

I was thinking about how when we move to a new country, things change. Our eating habits change, we try things that either fit or don’t fit, then we move on to the next. It’s the same when we encounter people. Some people we like and some people we don’t, and again we move on. It’s a natural process, so I was thinking of all that and these tiny boxes, and from that, it moved to creating a massive one.

RDS Visual Arts Awards 2018

The sculptures displayed in the RDS are a result of this process. I made a big box of plywood and I cut it and separated the pieces, so that when you put all the pieces together they become the original box again. Basically, this is my thought process; I was thinking about making origami pieces, I wanted not just one sheet of paper but different sheets of paper to come together to create one box. That would represent how different things come together to shape who we are. And then the disassembling of it; each piece would take its own shape and depth into a sculpture. It’s breaking down into layers, just like tracing each movement of the dance to create a sculpture. For the RHA show, there was the main piece, which I called the mother piece; all the pieces come from that one, but all occupied their own space in the exhibition. I did the same with the dance, and I broke down the dance process that created the groundwork for this series of works.

You can find out more about Anishta Chooramun work through her Instagram page & website, links below

https://www.instagram.com/anishtachooramun/?hl=en

https://www.anishtachooramun.com/