This interview was made possible by the Sligo Arts Service, Sligo County Council. To Celebrate the opening of Realm the accompanying exhibition to the Primary Colours Residency I sat down with the exhibiting artists and recipients of the residency Jo Lewis and Aideen Connolly to discuss their work and exhibition.

This exhibition developed from the Primary Colours residency, where each of you worked with different primary schools to create work. Could you talk about that?

Aideen: We were both assigned schools to work with, and I was lucky enough to be assigned the national school my children attended. The school is just out in rural Sligo near the Gleniff Horseshoe. There was a lot of flexibility in what I could do with the children. I had them make ink using natural materials, and on other days, we just spent the time up on the mountain (Gleniff Horseshoe) building shelters, drawing and foraging for plants to make ecoprints and cyanotypes. They didn’t see it as art, they saw it as play. And it was very connected with the landscape.

Jo: I was excited to get the residency especially as it was linked to an exhibition. Working with the children, it was so liberating to try things that were ephemeral. We would make works in nature from nature, work not made to last before being taken back by the landscape. It was great how the kids embraced this way of making because, so often they can get tied up with the concept of ownership. ” I’m taking this home; this is mine”. They really embraced the temporary rather than being very precious about the works they made.

We’ve talked a bit about the residency, but let’s talk about your studio practices. When you are in the studio, what are the first steps you take in creating a work?

Jo: The materials I use inspire me. I might have the urge to work with clay one day; or for example, at the moment, I’m working a lot with roots. Roots have influenced the work I’ve been creating for this exhibition.

In general, the materials I use are materials I’ve found. An important part of the process is finding the materials, bits of wood in skips or scraps that are left over. You see so much being thrown out. It always upsets me to see stuff being thrown out and not being used again. My partner is a builder, so he always has pieces of wood or other scraps hanging around that I can put to good use. I collect a lot from the garden as well. I’ve been collecting roots and seed pods and things like slices of cucumbers and leaving them out to dry to see how they end up looking. Where I’m at, at the moment, I’m using a lot of that garden waste. I wash the waste, like the cucumbers and roots. I think the act of washing them is so important because it gives you a chance to look at them. You get to look at them from a different perspective.

Seeing them from a different perspective has really inspired me to, in a way, play with the materials. Ideas have come from that, and I can push the materials in my work.

In the studio, I start by playing with different materials, and it is from that play that ideas will emerge. I develop by adding more structure to those ideas.

Aideen: If I’m starting anything, I will sketch first. It’s part of my research, how I’ll make the first mark. And I really like doing that, even if it’s only in one colour; I can get an idea fairly quickly and fairly cleanly. Sometimes they become the piece, but sometimes it’s just the practice of getting there, and both are equally valid outcomes. That’s the fun of it.

For this exhibition, I’ve been combining a number of processes: painting, drawing, felting, cyanotypes and my Eco-Prints. When creating ecoprints, I try and slow things down. You have to look at the plant and acknowledge it, know a bit about it. Is it poisonous? What colour will it be? I find that research, especially the practical research, is so important to my process.

Usually, I have to think how I will communicate an idea, whether it is going to be a painting, Eco-Print or Cyanotype. I explore, experiment and see where the process leads.

Have you had challenges working with natural materials, since they can change over time?

Jo: My work is very much about the experience anyway. An installation, no matter how big or small, will only last the amount of time you’re in it. With the materials I’ve been using, you could come into the exhibition one day, and a few weeks later, you might have a slightly different experience because something may have drooped, and in a way, noticing that change is an experience in itself. Those individual moments are important.

I’ve had some practical challenges as well, as you might expect, considering the organic nature of the materials. Pieces going mouldy, or things not changing in the way you expect them to, and to be fair, other things also dry out well. One funny challenge I didn’t expect was that some materials could look really well in the skip, but once you get them home, they aren’t so good. It’s very much about how you put things together and where they are positioned. But sometimes, you just have to accept that those changes are part of the work. I suppose if you want it to stay the same forever, the only way to do that is to freeze it in resin, but I feel it defeats the purpose of using natural materials.

Aideen: For me, If I want a crisp cyanotype, I have to work quickly with the plants, or they will wilt. The time of the year can provide its own challenges. There is plenty of greenery in the summer and spring and autumn, but practically nothing in the winter. Acquiring materials can be hard that time of the year. There are ways around that, berries can be stored in the freezer and plants can be dried.

When it comes to eco prints, the image is made using plant material as both image source and ink. The natural dyes and forms of the plant are transferred/printed on to cloth or paper through a process of wetting and heating. You have very little control. Yet, you are driving the process by putting the plant under pressure to release the pigment. I find it fascinating, as the plant can only do what it can do, so you are learning the plant’s limitations as you experiment with it. All plants have different compositions. I loved the exploration that comes with that. I had been making my own ink for many years. Combining my love of print with eco or botanical printing was a natural progression in my practice. Eco prints are mono prints!

Maybe we can finish by discussing your plans for the exhibition.

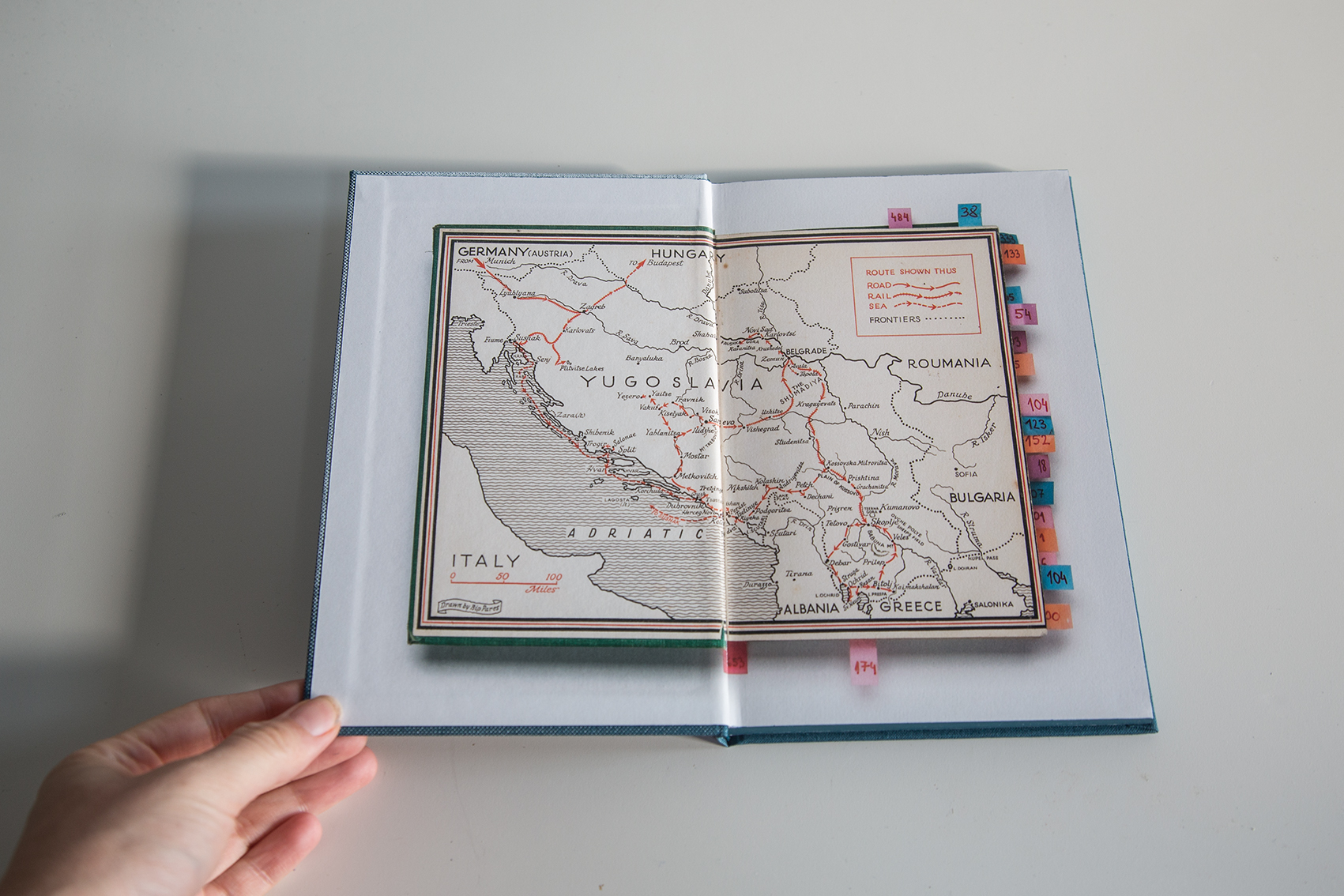

Aideen: My Realm journey is a linear map in a way, starting in my own townland of Cloonty (Meadow in Irish) through Edencullentragh/Hollyfield where St Aidan’s NS is located and up through the Gleniff Horseshoe Valley. The road passes through 7 townlands. Each townland once supported many families. Not even stones remain to mark each home. The flowers they planted fado fado do appear year after year though. I chose to forage at different times and places along the road for flowers, native and otherwise. Using cyanotypes (an early form of photography) and eco print techniques on paper, wool and silk, I have created work that gently echoes the ephemeral nature of its past.

Jo: Catherine Fanning will curate the exhibition. Whilst our work is separate we have elements in common, they will definitely complement each other. The Hyde Bridge Gallery has a lot of history. It used to be residential; the rooms still have the fireplaces from that time. I see recycled materials in a similar vein as they are objects that also have a history. Objects and spaces have embedded energy, and I plan to tap into that for the work.

You can find out more about the Primary Colours Residency through their Facebook page and website, links below

https://m.facebook.com/people/Primary-Colours-Sligo/100064312197104/

thank you, Anne James & Adrian Mc Hugh for your work editing