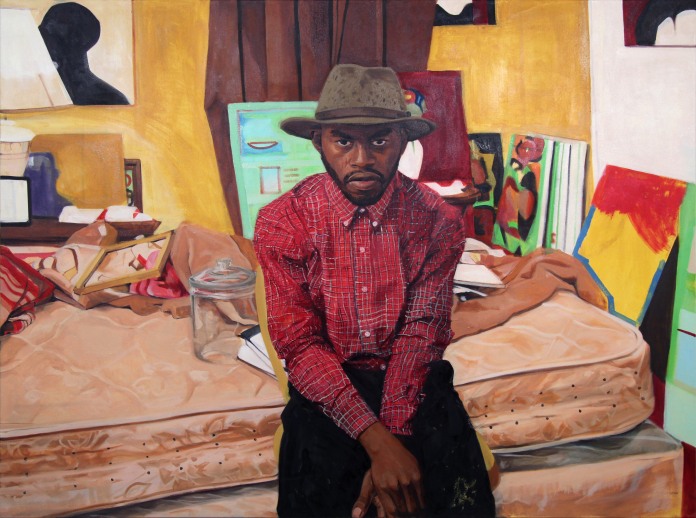

Shane Berkery is a Dublin based painter, Shane won both the Hennessy-Craig and Whyte’s awards at the RHA Annual Exhibition in 2016 and was one of the shortlisted artists for the Zurich Portrait Prize in 2019. I first came across Shane’s work around 2018 when I visited Dublin and conducted one of my regular treks of the galleries. I came across his work Somewhere between now and then as part of a group show that was in the Molesworth Gallery and it stuck with me ever since. I knew straight away that I wanted to talk him on his practice. One thing that struck me when talking to him is his drive to keep improving and keep pushing himself. In a way you could draw parallels to how athletes talk about their skills. He has such enthusiasm to explore the medium, and it was fascinating conversation with him.

I think the best place to start would be to describe a day in the studio.

I have a studio in my back garden, so I can wake up, walk the dog and then head into the studio. I get started around 9:00, and then I just paint. Right now, for instance, I have between eight and nine paintings at various stages of completion.

So you work on a few at a time?

Yeah, I’ve started doing that since my previous exhibition, (Cave Paintings). Before that, I’d work on maybe two paintings at the same time, max. But I’ve started a whole bunch at the same time because I find that when working on one painting the whole time, you stop seeing the painting. For lack of a better word, you become blind to it. So it’s good to just refresh by working on something else and then revisiting when it’s dry.

You describe your paintings as being a result of the process, rather than a goal that you reach.

Yeah. I don’t really approach each painting as a final product. Each painting isn’t the final product in my eyes. I approach each of them as practice. My final product is what I’ll eventually be able to paint, the artist I can become by getting better and better. The goal for me is to improve. Each painting I try to do something new. I try to start each painting a little bit differently from the last.

Eventually, I want to improve in all the components of painting. I view it as a form of visual problem solving. For example, I like finding colour combinations that I haven’t used before; I like to explore colour relations when painting. Obviously, composition is something I’m always working on.

I try different working styles as well. When I walk into an exhibition, I personally like to see different kinds of paintings. I like to see how far a painter can push their style in different directions. One thing I do want to do is get better at the representation side of things. That’s why my paintings a lot of the time have rendered representational elements to them. I still feel I haven’t mastered that.

Is there an element of challenging yourself?

I want to make something that I haven’t seen before. I think representation in the painting is a really strong tool. It draws the viewer in, and it gives a strong reference point for the viewer to place themselves within the painting. I like paintings that can do that, and that’s kind of what I want to do.

I think it’s just a continuation from when I was little. I’d just think about the figure in a painting, as an anchor almost. You can relate on a personal level. I find figures more engaging and interesting.

I think I’d feel pretty upset with myself if I stopped trying new things in my painting, so maybe it does circle back to challenging myself.

How important is scale for you in your work? I got to see A Light (2019) when it was in the Zurich Portrait Prize exhibition, and the scale really stood out to me.

I think there is a direct relation between scale and the impact it can have on the viewer, it obviously has to be done right though. Previously I worked quite big almost all the time, but with my recent round of paintings I have done quite a few small paintings where I can concentrate on specific elements and take a more targeted approach. I’m experimenting with that as well. I do enjoy making the big paintings though. And when I successfully do that, they feel way more fun to finish, and more of an accomplishment.

There definitely is a big difference between just seeing A Light on the screen and seeing it in real life scale, which it is. Tactility and all that disappears as well, when it’s on the screen.

And a lot of your paintings are from your grandfather’s photography. How did you approach that?

Yeah, I came across a whole bunch of them. I don’t know how many there are, maybe two or three hundred of them? I’ve scanned so many of them onto my iPad for when I’m working.

A lot of them are candid photos. The pictures themselves look like film noir stills. They were taken at a time when Japan was Westernising like America, and everyone’s wearing the suits like in the films. You see this juxtaposed against the Japanese landscape and the old traditional Japanese clothes that are still there. So, you see this unique mix of cultures that was fascinating for me.

It’s really interesting because there’s such a filmic quality looking at the paintings.

The process with black and white photos is usually, I go through all the photos that I’ve scanned until I see which photo jumps out at me, I then make a painting based on the photo – how it feels, how it looks. Once I pick the photo that I want to work from, it’s kind of like, OK, off to the races. And then I might have an idea beforehand that I want to try out, like a combination of colours, say really saturated red and green. Those colours are going to be kind of the starting point. You make decisions on the canvas, you take a colour, you go for it. And then from there it is a matter of problem solving.

Do you approach your grandfather’s photos differently, compared to the photography that you take yourself?

Yeah, I think there is definitely a different feel to it. And I think one of the things is that I tend to render lifelike colour in the photos that I take, because the colour is there, and when I have the colour in the photo I want to keep improving on that as well.

A lot of the pictures I take are of my friends, people that I know. My granddad would have taken photos of his colleagues from his company, candid scenes of them interacting. There are more formal family photos as well. A recent painting, the yellow painting (A Light) was inspired by one of the photos that my granddad took with the guy and the lighter, which I had already painted. It’s basically the same action with different figures. So I think I’m trying in a way to emulate what he’s done.

What camera do you use?

I actually have my granddad’s old Nikon camera that he used to take the pictures. I use that sometimes. And then I also have another 35mm camera and a Pentax 67 as well. It’s from the 70s or 60s. Medium format, big old camera. I enjoy taking pictures with film more than digital. With analog cameras, there’s distance between when you take the photo and when you see it, which I think is an interesting quality to that dynamic.

I know you grew up in both Japan and America. Do you think there is an element of representing those different cultures?

I think there is a different visual sensibility between Eastern and Western countries, and I think there might be something unique in borrowing from each side. But I don’t really care too much about representing culture in my work. I mean, when I paint my granddad’s photos, I don’t see it as painting Japan. I feel an affinity to my granddad, I feel a connection to the photographs.

At the end of the day, I’m going to draw from as much as I can. If something is part of my experience and the imagery is accessible to me, that will filter into my work.

You can find out more about Shane Berkery work through his Instagram page and websites, links below

https://www.instagram.com/shaneberkery/

thank you, Anne James for your work editing

You can support Painting in Text through Patreon, link below