Sophie Foster

Sophie Foster is an English artist based in Germany. This interview was recorded in December 2019 during her residency in the Leitrim Sculpture Centre. Her project Customs House was one of my favourite exhibitions I had seen in 2019 – for me, the way Sophie was able to deftly balance audience engagement and authorial intent was a key aspect of why the exhibition succeded. In this interview, Our conversation predominantly focused on Customs House, but that project provided us with an illuminating discussion about Sophie’s practice and approach to art as a whole.

Can you talk about the start of Customs House, the project you did in the Leitrim Sculpture Center? This idea of getting visitors aid in exchanging natural materials form one side of the Irish border to the other is fascinating?

I started by researching what other artists had done in the space there definitely seemed to be a lot of socially engaged practices being exhibited. I think a lot of people are intimidated when they go into this typical “White Cube” space, so I try to allow the viewer to put their input on what they are seeing. Something that influenced what I ended up doing was finding out the gallery used to function as a shop. I think the shop idea allows the project to be more interactive. Filling in the invoice or deciding the object they want to bring in, giving them that choice. So, they can read into the project. I always like to get this kind of feedback from people because it brings different perspectives which allows you to develop the project further. And with Customs House it was broaching a heated subject like the Irish border which had a number of perspectives.

CUSTOMS HOUSE, (2019), Exhibition Installation shot. © Leitrim Sculpture Centre. Photo by Sean O’Reilly

When I apply for residencies, the place is paramount, and my practice, in general, is responding to location and the context around the area that it is in. So with Manorhamilton, seeing how close it was to the border, instantly a light switch went on in my head. I could do something with this. And I don’t know if it is a good thing or not, but it is something that artists should be aware of or play to their advantage, you are always going to be typecast with background, and I found that when I moved to Germany. I had moved after the 2016 referendum, and the three questions would always be asked were What’s your name? Where did you come from? And what did you think about Brexit? Brexit is this big huge word that I cannot escape. Because of that, I also thought of timing and how this border was affected by this vote. I wanted to know how people felt about the situation. I had seen it on a map, I’d never been there myself and talking to people who cross it every day. People of different generations who have lived with it and experiences they have had and how they have dealt with it has been really interesting, and it has been so nice to get a broad range of different ages and groups of people. Borders is a vast topic that genuinely interests me. These socio-political situations and their relationships to geography. This felt like the perfect opportunity to develop that idea.

The Lines of Exchange. Part of CUSTOMS HOUSE, (2019), screenshot. © Leitrim Sculpture Centre.

One aspect in particular with Customs House that intrigues me are the trades, could you talk a bit more about that?

For me, the exchange is about determining what is equivalent, in terms of value. I’m quite interested in the importance of objects and the power of objects. And that can be for many reasons, and this is something I discussed. What is value? something rare or something that is expensive, unique or has sentiment to it. So, it is playing with that and the irony of you using natural materials which are seen as plentiful. You can go out and pick a stone up and say that is just a stone. But then, of course, every stone has a uniqueness to it. Then by rigorously categorising everything, putting stuff in jars, measuring and adding the location of where the object is from. That adds that uniqueness of every object. In a sense, it becomes something else. Rarefied.

Filling in the Invoice. Part of CUSTOMS HOUSE, (2019), Documentation from the exchange event. © Leitrim Sculpture Centre. Photo by Sean O’Reilly

I was looking at the apothecary idea of using natural medicine and putting this kind of context behind the object and this idea of value. The Customs House idea then brings in a purpose to what the people are doing at the shop counter and the person behind the counter with the white coat on. It contextualises the trading. Whereas if I just put a table in the space and had the objects laid out without purpose, I don’t think there would have been the same level of engagement. And then you have the invoice, this element of bureaucracy. And you have to fill in the invoice, that’s like the task. You have the written record of the exchange, and that can link into many political situations of trade and exchange as well.

CUSTOMS HOUSE, (2019), Exhibition Installation shot. © Leitrim Sculpture Centre. Photo by Sean O’Reilly

You might think of someone just walking and just picking something up and bringing it in, but I’m giving them a choice to bring in whatever they want. I think that has been very interesting to see why they chose the objects. Whether it’s something that they feel is beautiful or because it reminds them of when they go walking. It might have some kind of relation to the place. Quite a few people have written in the value bit “I chose this item because it reminds me of home”. Or “I chose a bit of wood from the tree my kids used to play on”. You know there is a tremendous amount of sentiment that I wasn’t expecting. But that’s what people decided to focus on, which links to themes that I’m interested in. In memory, I think that’s the power of the object, isn’t it? You don’t want to forget something or lose something

What happens to the objects at the end of the exhibition?

CUSTOMS HOUSE, (2019), Exhibition Installation shot. © Leitrim Sculpture Centre. Photo by Sean O’Reilly

The third room where you can see the objects on the shelf, they are placed back into the landscape. And the plan is to put the objects in their new location and document that as well. I think having that documentation is helpful for people to be able to see in a photograph – oh, my object went there. That knowledge is quite nice. To have been a part of something, this bridging exercise. For the audience members that exchanged an item, it’s up to them what they do with their object. Most people take them home. Others have said that they will take it to the location where they found their objects.

Relocating the Objects of Exchange. Part of CUSTOMS HOUSE, (2019), photo documentation. © Leitrim Sculpture Centre. Photo by Jackie McKenna

The exhibition wasn’t just your shop front. You also had a chalk representation of the border as well.

The Borderline. Part of CUSTOMS HOUSE, (2019), Exhibition Installation shot. © Leitrim Sculpture Centre. Photo by Sean O’Reilly

Yeah, that’s right. So, the borderline when you see it on a map, it just looks like a squiggly line, it kind of doesn’t even make sense in a way, why it’s there but then I realised when I visited that part of the border between Belcoo and Belleek, a lot of it is water, so it made sense having the River there as a natural stopping point. It makes you wonder how borders are drawn up. Politically it’s a game. But particularly with the Irish border when you’re physically there you cannot tell. That for me was quite interesting because not all borders are like that. Specifically, at this time of year where we’re commemorating 30 years of the Berlin Wall falling down there are more walls than ever! I think it’s quite lovely to visit a border that’s kind of physically not there and people are free to cross it. The idea of drawing it with chalk on the blackboard was because it can be rubbed off, so it’s actually a way of physically representing how some people feel about the border. I think with the younger generations who didn’t live with the troubles, who have lived there their whole life where it has always been open, it’s kind of invisible to them. The border might not mean anything to them compared to the older generations. One visitor said, “Well the border for me was this rite of passage. To be able to physically cross it was a huge thing.” Because for them, it wasn’t always so easy.

Mark Making is obviously very important to you.

That goes back to my degree. So, I studied Combined Honours where the drawing was the third component which included Art history. And I pretty much just did life drawing. Which I enjoyed but, kind of felt I couldn’t develop it in a sense. You’re drawing the figure again and again, occupied with proportion, and getting the figure right. This idea of mark-making came about from this idea of the happy accident. Of drawing as doodling when you’re not trying to think of anything you know, taking the pen for a walk and creating these interesting lines and shapes that stem from that. Thinking about not just what you are drawing with, but what you’re drawing on. Paper as a material itself and what you can achieve with that either making it or allowing it to decompose or using different instruments to create certain marks and lines.

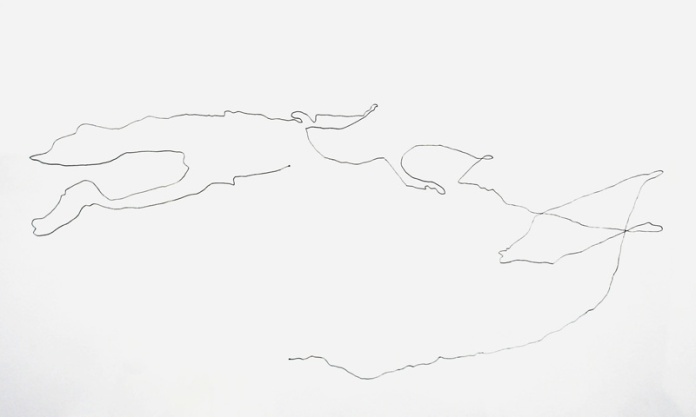

Trail Drawing, (2014), ink on Japanese paper, 80×60 cm

And that kind of developed further when I was doing a residency in Northumbria University in a paper studio, because I learned the craft of making your own paper. Once you put the energy into making your own sheet, paper suddenly become so precious that you don’t want to draw on it! So that kind of stemmed from that really, I don’t do so much drawing anymore, but I think it’s the planning stages when it really comes about – just trying to get something down on paper or coming up with ideas I find that can be a useful medium. And it shows through so much in character and personality to see how people draw and how they are with their lines and stuff like that.

And repetition is also something that I’ve been interested in a lot, giving yourself a kind of task like for example I’m going to draw 100 lines, or I’m going to colour in 100 squares. For me as an artist, it’s very important to do things that are quite physical or time-consuming or requires an element of energy and physicality so then I feel that I’ve achieved something by doing. So I often give myself these rules to try out and follow. I like to be organised, and I like to have structure. It’s super important. I just can’t go out there and draw or do something. Research has to be put into it, so I know what I’m doing. And for me, it makes it all the more worthwhile that I am working towards something.

Let’s talk about your research process.

Yeah, I’m hugely research-based for sure. And I enjoy doing that. So how I tend to work now, there’s this element of place or having a place to work within, a building or something like that. Then it would be researching into that, like the history, the society, the other contexts that’s around it and then from that, the creativity starts.

I get a lot out of being physically in the place as well you know, interacting with it. I found with this, The Customs House, I purposely chose to cycle and walk to get to the destinations. To actually feel like I’m involved and experiencing the landscape in this physical kind of way. Like cycling up those hills and down again! Cycling 20 kilometres to get to the border. And I also read a lot of literature around it too. For this project I’m reading The Ballroom of Romance by William Trevor. It’s about the Rainbow Ballroom in Glenfarne on the border. A lot of people cycled through It, and I wanted to experience that as well. But it was interesting to physically be there and try and find things, go to tourist centres and talk to people about the area, it’s a kind of practical research, To physically be there is part of the research as well.

There is definitely a sense that the environment is very important to you within your work.

I think it’s just this enjoyment of being outside! I don’t like being cooped up in the studio. I find it very isolating, I just find I get a lot out of it personally being with the environment or trying to work with it in a sense rather than against it. I always find a lot of beauty in natural things. And I don’t really want to replicate that myself but kind of use it as a way to influence my work or allow people to see things differently. I think that’s the main reason why I keep coming back to it. Also, there is a massive amount of philosophy and science behind nature and natural forces and the weather, it’s something culturally that we’re really obsessed with. It rules everything, and we can’t control it. That just shows how powerful it is and how small we are. It’s definitely something I want to develop further, bringing an awareness to environmental issues.

You can find out more about Sophie Fosters’s work through the links below

https://www.instagram.com/sophiefoster_org/