Darren Nixon

I met Darren Nixon when he was working on Dislocate for the CCA in Derry~Londonderry. Funnily enough our meeting was a chance encounter that I hadn’t prepared for in advance. But I got talking to Darren and really got sucked into a fascinating back and forth discussion on what relationship artists has with their audience. (Remember, this was my first time meeting Darren!) He converses with such openness, and honest that was really refreshing and disarming in a way that gets you to engage back in an equally open manner. Getting to talk to Darren for the interview really made me aware of the wealth of knowledge he has, but treats you like an equal and never talks down to you. I gained so much from the interview, and his process is something that we can all benefit from even when simply appreciating art.

Your pieces are often a mix of sculpture installation and video, but it feels like painting always shows up in some element. Let’s start with your relationship with painting.

I kind of still think of myself as a painter. Most of what I do starts off with painting of some description. And I suppose I’m slowly getting to the stage now where I’m starting to wonder if paint needs to be a part of everything that I do. What I’m thinking about a lot of the time is the relationship between different ways of working. Because paint is naturally the language that I speak, when I think about something, paint is the starting point for thinking about work. When I work in other ways, how that differs from paint, and the possibilities and tensions between those, are what interest me. In a wider sense, it’s thinking about how the medium that you use affects the thoughts that you are able to have.

That’s why whenever I’m not sure where my work is going, I just go to the studio and put paint on stuff while I think. Because it’s just it’s a way of thinking for me. But in the work itself, and the actual act of painting I’m increasingly putting some distance between them.

I’m starting to think of the painting process as what happens after the bit where the paint goes on the stuff. But regardless of what I’m working with, I feel like I work in quite a painterly way.

With The Audience, you combine sculptural elements along with painted portraiture. There are elements of art history within that.

The Audience installation shot at Rogue Studios, (2016),

Mixed Media. Dimensions variable

When I’m trying to think about things with a bit of nuance, it’s easier to frame that idea in the context of what people understand, so, “How does the audience look at a piece of work and what does it mean to have the work look back at them?” I was looking especially for that piece to Dutch portrait painting at that point where painters, for the first time, started painting faces which looked back at the viewer directly and what this meant as a shift in what people expected from art.

I suppose the process is quite different for each piece, but with something like that, part of it is I just want an excuse to paint. Because painting seems harder to justify, just for its own sake. But I love doing it.

I often think about the failures of painting, the directions, and the dead ends that it’s walked itself into at times. The functions that it was used for and all the vitality that it used to have, and how it’s not the go-to to think about a lot of things like it used to be. It’s not the primary way that people understand the world by and large anymore. It’s not the way people understand landscape as much as it used to be. It used to be the central tool to explore these themes for a lot of art. That really interested me; that, and what it meant for me making work and how the audience processes the work.

How do you view your relationship with the audience?

It depends on the piece that I’m working with. I don’t overly worry about things being tremendously evident in the work, but I like there to be some element of clarity in the work. I like to think that the things that I’m thinking about are there within the piece if you are looking at it, but, I guess not everyone is going to walk in and respond to it or spend the time to get to know the work. And not everyone’s going to get the references I’m making. That used to be something that bothered me enormously; now I’ve moved past it. I remember being obsessed with the idea that if my mum or aunties didn’t understand the piece I was working on, then there was some failure on my part. At some point, I guess art has to be able to move to other places, and you can’t take everyone with you.

There is definitely an element of art about art within my work, I suppose, and that leaves some people cold. Rather than trying to make the specific things that I’m thinking about really clear to everyone that looks at the work, I’m kind of interested in them just seeing the process of thinking laid bare. So, each piece is a process of a way of thinking.

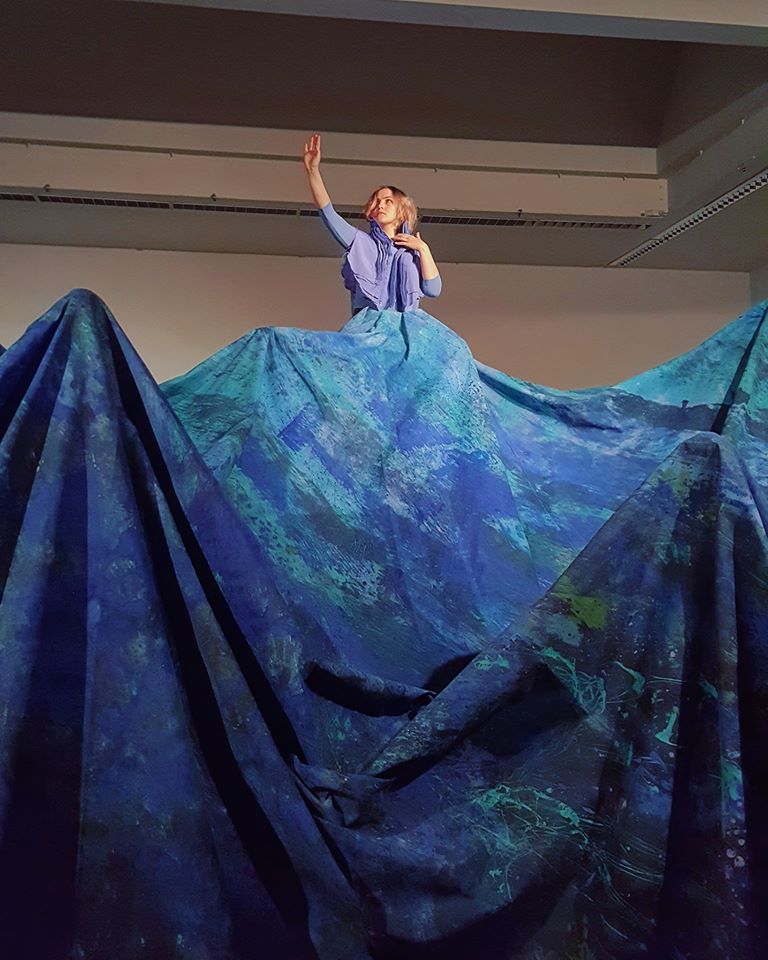

The Difference Between Dancing and Contemporary Dance, (2015)

Mixed Media, Dimensions variable

One of the first pieces that I did with this in mind was a piece called The Difference Between Dancing and Contemporary Dance. It was about my complete lack of connection or engagement with contemporary dance, despite being somebody who loves dancing and going out. So on some level, I thought me not getting this was not OK, because there is obviously something going on there and I am not getting it. For as long as I spent making it, I just looked at tonnes of contemporary dance until I found stuff that made sense to me. When I found the work of Jerome Bel, Anna De Kersmaeker and Siobhan Davies Dance company it opened a door for me into contemporary dance that I really understood and connected with. My pieces are like a record of my research and my thinking while doing this research. I don’t think you look at that piece and gain some insight about contemporary dance that you never understood before, but it was a vehicle for me to develop an understanding of contemporary dance, and I’m sharing that journey with the audience.

And since then, dance has become something that I’ve become even more interested in which has influenced later work. I suppose some pieces like that are almost small projects, almost like a little bit of an excuse for me look up stuff and broaden my horizons.

I want to know about things. And that often progresses to, “How can I make a piece about it?”

I’ve been trying on and off for a while now to think of a piece that would allow me to do the same thing with poetry. Because I love reading, and I love literature, but I struggle to gain a connection with much of the poetry I read. And yet considering my fields of interest and finding the way I think about evocation, and the relationship between words and imagery, poetry is something that I feel I should be able to connect to, but I just don’t. At some point, I’m going to try and do a piece that will give me an excuse to dive into it. The driving force behind most of this is understanding what it is within myself that prevents me from really understanding something. It’s a lot of self-exploration.

I find thinking about stuff that I don’t understand and don’t feel an attraction to more inspiring than thinking about the things that I love. If you engage with something that you really hate or don’t connect to at all, and just spend some time really thinking about what it is…it’s not necessarily the work, it could be you. You can learn as much about the shortcomings in your understanding as about any shortcomings in that work.

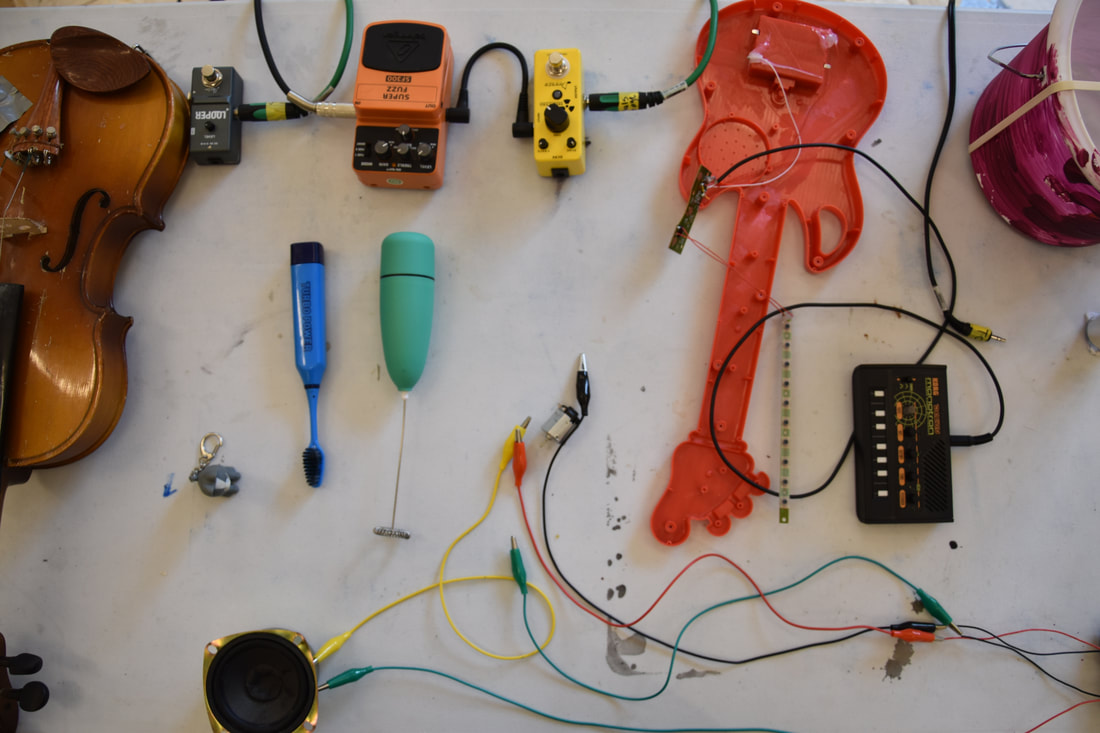

It’s evident that collaboration is really important to your work.

When I first started collaborating with other people, there was definitely an element of the agreement that they either had skills that I wanted to bring into the work or learn myself. As we worked and I watched them do their thing, it began to felt like an exchange of skills. When I did my Standpoint residency, I decided that I would work with people who were involved in movement because I knew I was interested in movement through the objects that I was working with, but I hadn’t been happy with my results. So I set myself up in a way to work with a broad range of people to try and watch them and learn something from what they did, but at some point, I stopped trying to gain specific things out of it and allowed it to be itself and expand into its own thing. When you started to watch the whole picture of what was happening and the generosity that people brought to the space, the amount that they poured into my work and the amount that they trusted me, the actual act of negotiation became fascinating to me. Skills from my day job – where I often work with the general public – that I never thought would have been of any relevance to my art practice, came to the fore. Like my ability to put people at ease and read the atmosphere in a room and read how people are responding, they became vital tools in making the work happen.

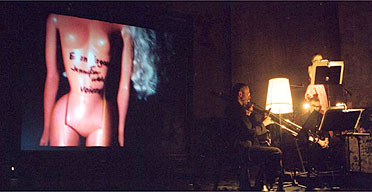

Host at Chisenhale Studios London 2018 from a series of collaborative films recorded across six week period with 18 invited guests

And so the actual act of collaboration and negotiating with people became a central part of what I was interested in. That moment of transformation whenever you’re in a room with somebody, and you come with a loose enough layout and you don’t try to push your agenda. You don’t try and make a specific thing happen; then you have all that trust and there comes this moment where something happens in the room, and it becomes filled with this other energy and your connection with the person becomes an entirely different thing. Those moments felt like the completion of the work for a really short period, that fed into my idea of wanting to make these kinds of non-art objects that are never quite settled, so they just became an extension of that idea. In some way, the work is only ever complete for these brief periods, with these people.

Working in this way I have learned how important it is to find ways to allow the voices of the people I am working with to stand on an equal footing with my own. This means trying not to overburden them with too much sense of where I am coming from or what I want to see happen. Where things go is something I want us to find out between us. So there is sometimes quite a tricky process of negotiation, trying to figure out how much information they need to be able to invest in the process without giving so much information that they feel like the process belongs exclusively to me.

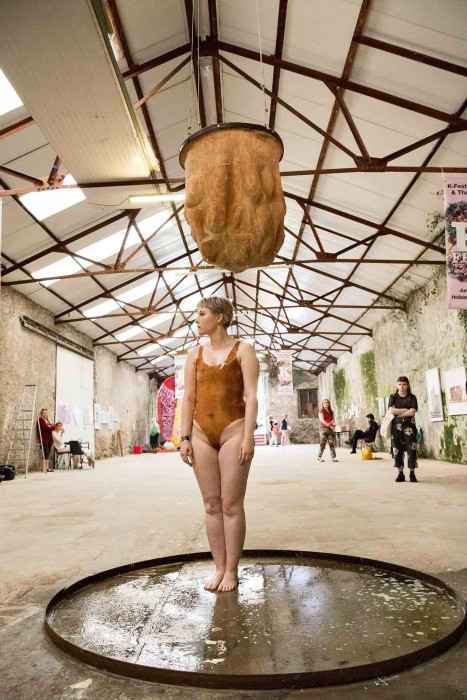

Dislocate an offsite project with CCA Derry~Londonderry, (2019) featuring Janie Doherty & Lydia Swift a series of films recorded over two weeks,

When you have someone like Janie Doherty or Lydia Swift who is prepared to go to that point, and is prepared to end up with these things happening that are nothing like what I envisioned when I was making the objects in the works, those times are precious. The time you spend with those people seeing how they negotiate the things you made and seeing their creative approach is a great privilege. That act of negotiation has become the centre of what my work is about. That time in the room is as important as the resulting art piece.

Dislocate an offsite project with CCA Derry~Londonderry, (2019) featuring Janie Doherty & Lydia Swift a series of films recorded over two weeks

Could you talk a bit about a day in the studio?

When I am in the studio, I do spend a longish day there. I used to spend most of my hours working in the studio. I used to work in central Manchester and also have a studio there. So I would go to work nine to five, then to the studio, stay till eleven and cycle home. Then on days off, I would cycle into the studio about ten in the morning, and I would stay until ten at night. So it was like most days, if I have a full day I would do a twelve-hour or more day in studio, partly because the things that I was making, stuff like The Audience, take a long time to paint! I think it was about 140 faces? So, it was hundreds and hundreds of hours in the studio painting! I got really good at painting faces throughout that!

With the arrival of video in my work, however, my time is now split between working in the studio and working at home. I sometimes find it difficult to strike the right balance between these two because video editing and figuring out what to do with the stuff I film is such a time-consuming process. I prefer being in the studio painting stuff but sometimes I can go for weeks without having much of an excuse to be there when I am pulling stuff I have filmed together and that needs all my focus.

The material that you use is quite interesting. How do you choose the materials that you are going to use?

For the past couple of years, I’ve almost exclusively used stuff from skips or discarded stuff left on streets or around spaces I have been working in; making these big expensive things involving a lot of material started to make me feel a bit uncomfortable with buying new material, because of the amount of waste involved. I wanted to keep making these installations, but only making them using stuff that was bound for the bin or that someone else had used previously.

Generally, it has to be able to take quite a lot of physical punishment. I also have to be able to repaint them after each session and have them ready for another session. They have to be quite easy to move which is also partly why they end up quite simple. It has to be something that I can easily reconstruct and redo because it could be used across a few months in different spaces. When I feel that I have gone as far as can be with the bigger pieces, I will then cut them up and re-use them for others. Apart from the practicalities of using cheap reusable materials for my work it is also quite a conscious rejection of some of the preciousness around materials that persists especially in painting. How fetishy some painters get about paint, I understand why, because it’s the material that they’re using, but when I listen to painters talk about specific glaze mixes and these paints they got from Holland it just bores the **** out of me. For me, I think of paint more as colour that I can put on things that will also protect objects that I’m working with. It’s the act of putting paint on an object as a way of thinking about the act of an object travelling from being in the everyday world into the world of art in a really simple way.

The whole point of me starting to work on objects rather than canvases was that I just really wanted to explore space, and why space is so central to how they operate. That’s the whole reason I’m there is to try and find out something about space that I don’t know, or something I don’t understand already. Because they take quite a while to set up, and so it feels still quite like early days with these ways of working. And I’m excited to see how it progresses.

You can find out more about Darren Nixion’s work through his website, link below