A key aim of Painting in Text has always been to get different perspectives on art practice, and with that in mind I made a concerted effort to look at artists outside of my own personal experience. It was through those efforts that I came across Yasmine Nasser Diaz, a multi-disciplinary artist based in Los Angeles, CA. The way she combines different element’s not only in her collage but in her installation work is so deftly done. It was such an enjoyable experience talking to Yasmine and I am glad I got the opportunity.

Let’s start with your recent exhibition, ‘soft powers’.

‘soft powers’ builds upon work from the last three to four years. The show itself consists of two main parts: an installation and a series of fibre etchings.

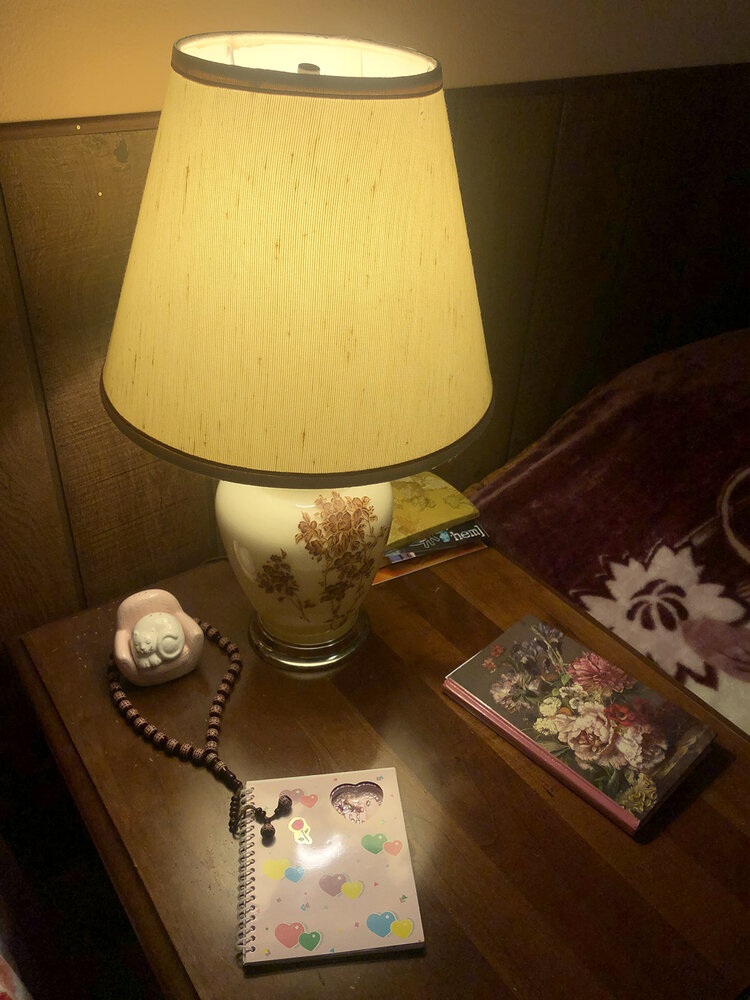

The first iteration of the installation was for the 2018 exhibition, ‘Exit Strategies’ at the Women’s Center for Creative Work in Los Angeles. I recreated a semblance of the teenage bedroom that I shared with my sisters. The details in the room span a range of time periods as there is a large age gap between my sisters and I and my family lived in that house for close to 30 years. The wallpaper and wood panelling were from the 70s–wood panelling being common in Chicago basements. Most of the pop culture artefacts were from the 80s and 90s when I was a child and adolescent.

The installations have always meant to be interactive. Visitors are encouraged to listen to the cassettes and spray the perfumes that were popular in the 90s. Scent is the most visceral way to conjure nostalgia and memory, it can be a kind of instant time travel. The installation for ‘soft powers’ is different in that it is not autobiographical. I created a fictional narrative to build the room that belonged to a pair of Yemeni-American sisters, Dina and Saba. I enjoyed using fiction for the first time because it allowed me to inhabit multiple voices. I was fortunate to collaborate with author Randa Jarrar who wrote the text for the sisters’ diaries. We developed storylines that spoke to the complexities of adolescence – coming of age and trying to find yourself while also navigating these seemingly disparate worlds.

Can you explain what you mean when you talk about disparate worlds?

This is where the title, ‘soft powers’ comes from. The term is typically used to describe a strategy in diplomatic relations, the ability to attract or subtly persuade someone to get what you want or need. I’m nudging that interpretation a bit to refer to a skill that we begin to develop as children when we first start to learn how to adjust our behavior to achieve a desired result. You could say this starts when we identify which parent we can get we get what from. I’m honing in on the more nuanced skills of children of immigrants, specifically those of families who migrated from the Global South to the Global North. For many of us, the home and what exists outside of the home are two very different cultural worlds. I, for example, was born and raised in Chicago, in a pretty tight-knit Yemeni community. At the same time, I was attending public schools that were extremely diverse with classmates of many different ethnic and religious backgrounds. The U.S. is more of an individualistic society compared to the community that I was being raised in at home, which is very collectivist-minded – decisions are often made in the best interest of the family and the community.

These different worlds convey disparate messages to young people still forming their identities and values. I’m not advocating for one way over the other as there are pros and cons to both. There were challenges though in navigating between a society that prized individual expression versus one which valued the community and tradition more. I learned how to behave ‘appropriately’ in both worlds, like many young women do. We’ve become very adept at switching between environments. People talk about code-switching a lot these days, which usually refers to language, but I think that it can apply to so much more. There is also what we decide to share in line with the way we want to be perceived. That’s what I mean by ‘soft power’: the various and nuanced ways we refine the ways we communicate.

You mentioned that this is the third time you have installed the work…

That’s right. The first was ‘Exit Strategies’ in 2018 and the very next year, I installed ‘Dirty Laundry’ during a residency at Habibi House in Detroit. There are changes with each iteration. I thought that Detroit might be the last time because those first two versions were directly autobiographical and the process of creating and sharing the work was pretty taxing. I had, for the first time, shared some intensely personal details. For example, after I graduated high school, I left home with two of my sisters and we were basically estranged from our family for a very long time. We did not see the rest of our family for almost 20 years. I included references to that part of my past in those first two installations – some documentation of our name-changing process and correspondence during a period when I was trying to get legal help. In the process of sharing the work, I met with visitors and spoke about it quite a bit. To talk about these things repeatedly was emotionally exhausting but in ways also cathartic, it has been rewarding in so many ways.

I’m aware that I am often the first person of Yemeni background that people meet, in Europe or the US, so I often feel the need to clarify that although forced arranged marriage and honour violence does exist in our communities, they are certainly not faced by all Yemeni women. I don’t ever want my personal experience used in a way that adds to the xenophobia that exists in the world. Nevertheless, these are issues that our communities don’t talk about enough. It’s a precarious place to be.

When the Arab American National Museum saw my installation in Detroit and invited me to do a solo show, I reconsidered my stance on not creating another bedroom installation. It was extremely meaningful to have an opportunity to bring a conversation that centres Yemeni American adolescence and girlhood to an institution that is important to the community. The first two iterations were in community-oriented spaces, the Women’s Center for Creative Work, a wonderfully supportive community, and then at a grassroots residency in what was essentially someone’s home. The Arab American National Museum is in Dearborn Michigan, right next to Detroit. That area has the largest Arab American population in the United States, which is very relevant to the context of the work. My parents immigrated to nearby Chicago in the late 60s so the area is essentially an extension of home.

While this installation is not directly autobiographical, it still draws heavily from my own background. Working with fictional characters was liberating. While I feel that all work is somewhat autobiographical as you can’t help but be a part of what you create but fiction can make it a little easier. I think that almost every person holds different identities at once and I love how fiction can be a tool to mine from different parts of one’s self. There is so much freedom in it.

Before going further, it might be good to describe the process of fibre etching for those who are unfamiliar..

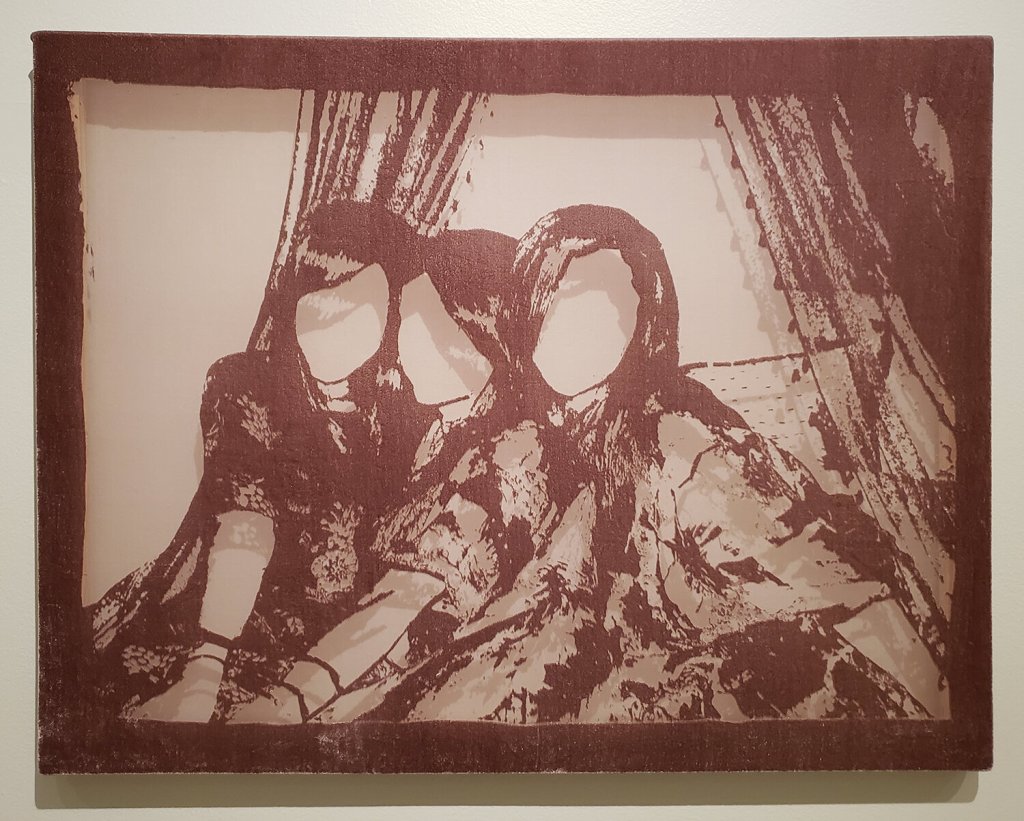

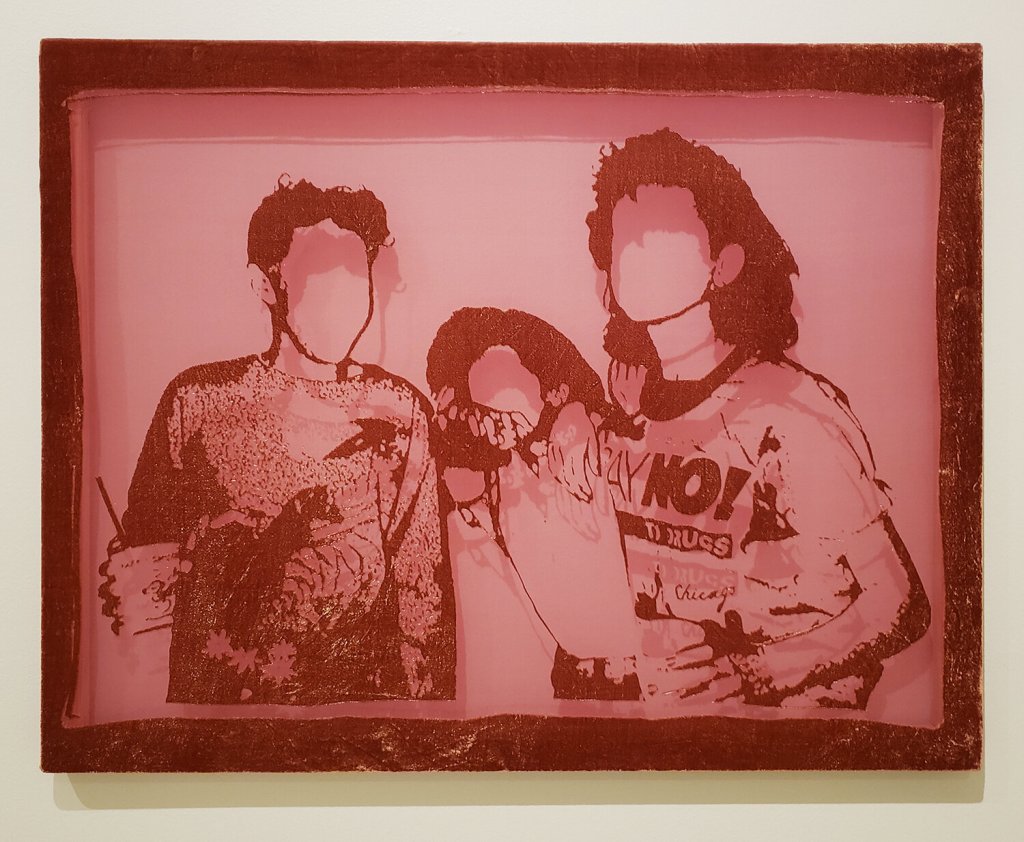

I like to call them fibre etchings because the effect is not like the industrial velvet burnout that people are used to seeing in clothing or drapery. This is done by hand, and it’s pretty labour intensive, especially when it comes to the larger pieces. I mostly use velvet for [the etchings] but have also used other materials like satin. Basically, the fabric has to be a composite [made of two different kinds of material], in this case I’m using mostly silk-rayon composites. It’s a reductive process wherein a chemical removes the rayon portion, so the silk backing remains. Some parts of the fabric remain opaque while others are more sheer. I use personal photographs as source material to create the images.

Where have you sourced the photographs?

They are mostly my own personal photos from around the time I was in high school. There’s a relationship between the fibre etchings in ‘soft powers’ and the collage pieces in ‘Exit Strategies’. Both feature images of my sisters and I in our bedroom with our faces removed, which I’ve done for several reasons. The space and context is quite vulnerable to share, as is with all of the personal details. The anonymity essentially serves as a layer of protection. In some cases, it has allowed me to use images that I might not otherwise be able to use. The scenes are intimate and the photographs were not taken for public consumption. I was also thinking of the censorship of images of women in certain parts of the world. The removal of the face is a kind of censorship but it’s a censorship within my control in support of my own intentions.

For ‘soft powers’, I sourced images, not only from my archives but also from other Yemeni American women, some of whom were family and friends. They allowed me the privilege of going through some of their photo archives. I was looking for snapshots of women-identifying people taken in their own spaces – casually hanging out in bedrooms or other private spaces where they didn’t have to worry about who else was around. I think it is true for girls of all different backgrounds that our bedroom spaces are something very special to us.

In my experience, Yemeni immigrant communities tend to be more insular than other Arab groups. They are generally more closely-knit and socially conservative. For young women, these spaces become even more of a sanctuary where we can let our guards down and be ourselves. These photographs are taken by us, for each other. They are seemingly mundane and affectionate scenes of girls passing the time, that is what I wanted to focus on in these etchings.

Your work plays with the idea of creating empathy through familiarity. Can you talk a bit about that?

I think there is instant familiarity in these spaces. When I was first considering talking about some of the more sensitive subjects and sharing some of my personal documents, I had a lot of anxiety. I knew the risk of being made out to be a representative of the Yemeni experience even though that has never been my intention. I wanted to talk about some of the issues that are important to me through the construction of a space that had a sense of nostalgia. Bedroom spaces invite a natural feeling of comfort but I included things that complicate that quality of comfort and nostalgia. There are memories that I recall fondly from that time and others that are very troubling.

When people enter the space, the first things they tend to notice are the signifiers of another era – the groovy wallpaper, the fun pop-culture artefacts. Upon closer inspection, other details emerge that tell a story more specific to the room’s inhabitants. Even though the viewers know it’s a fictional space, there is still this feeling of voyeurism that makes them pause and question, “Should I be in here looking at this diary?” It triggers an instinctive feeling of empathy and can be an effective way of communicating. Nostalgia has such a wide range of associations for people, and I certainly don’t think all nostalgia is inherently good but I’m thinking about it in both a fond way and a complex way.

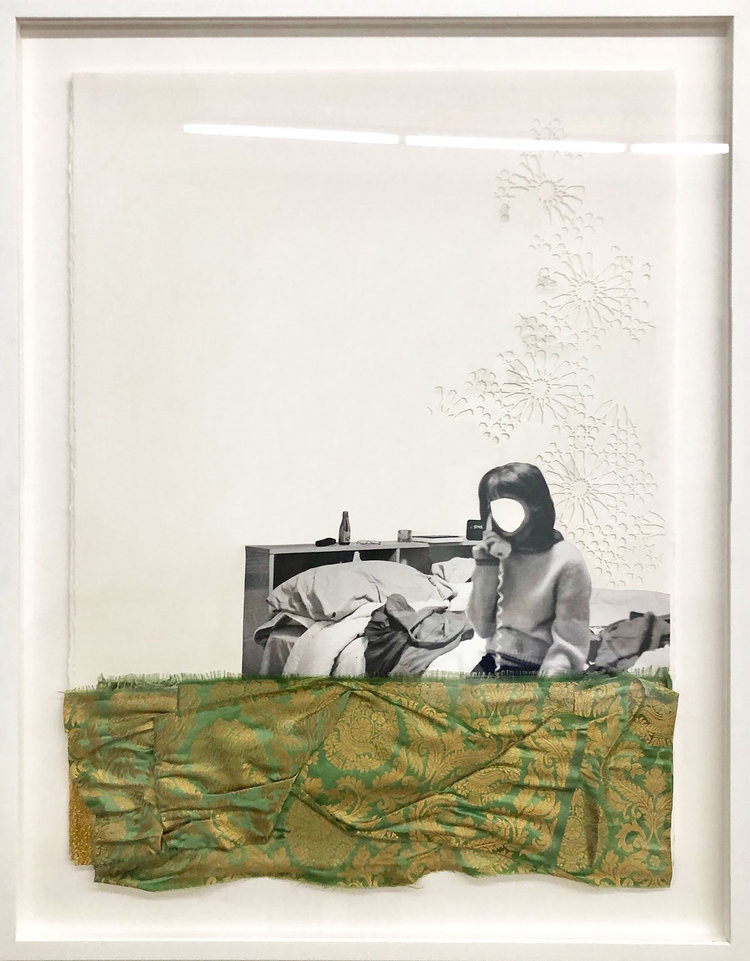

Has collage always played a part in your practice?

Collage is still relatively new to me. I was primarily painting before I got into collage about four years ago. I found the shift liberating. I experienced a playfulness that I hadn’t felt in a really long time. It was similar to that uninhibited feeling we experience as children when we made art without overthinking.

I see a lot of similarities between the process of collage and the experience of being an immigrant or child of immigrants. You are often taking materials from different places and putting them together – images and source material that seemingly have no business being together forced to live in a new place. It’s an apt medium for telling some of these stories. I try to keep that feeling of playfulness in my work by doing a warm-up collage when I get to the studio. I’ve started doing a little workshop around this; it’s very simple and there is no intention, just like that feeling I had when I first started collage. It is very easy for artists, once they hone a technique, to lose that feeling of playfulness. I want to maintain that and continue to access my intuition.

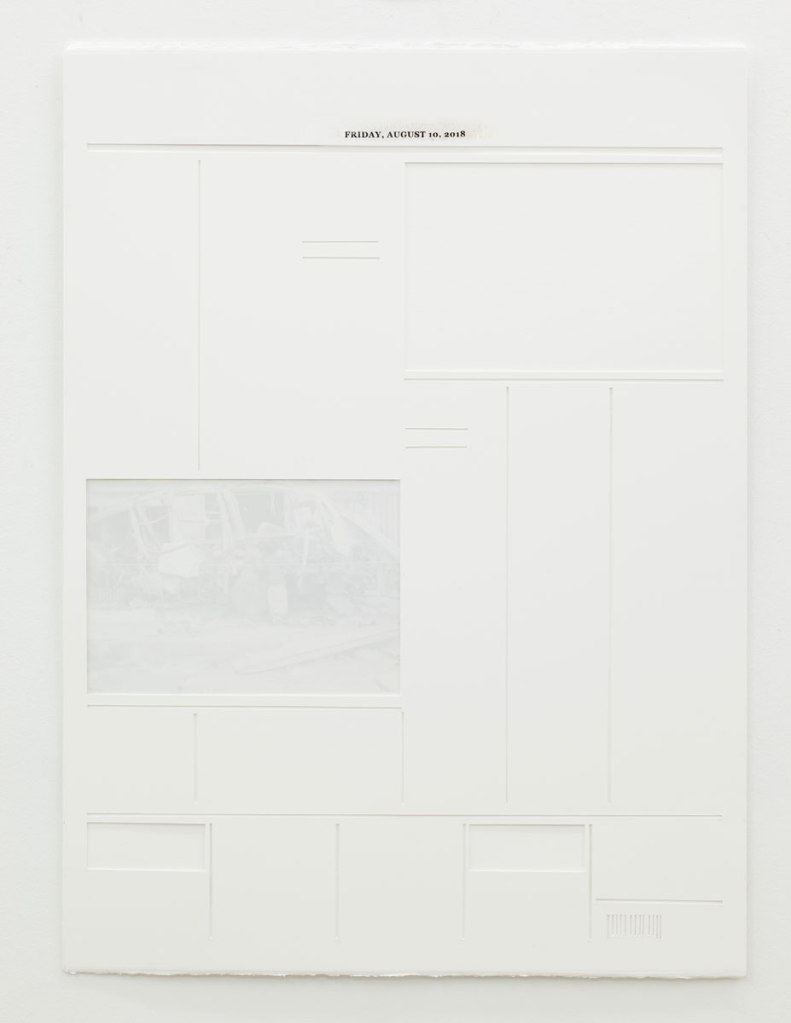

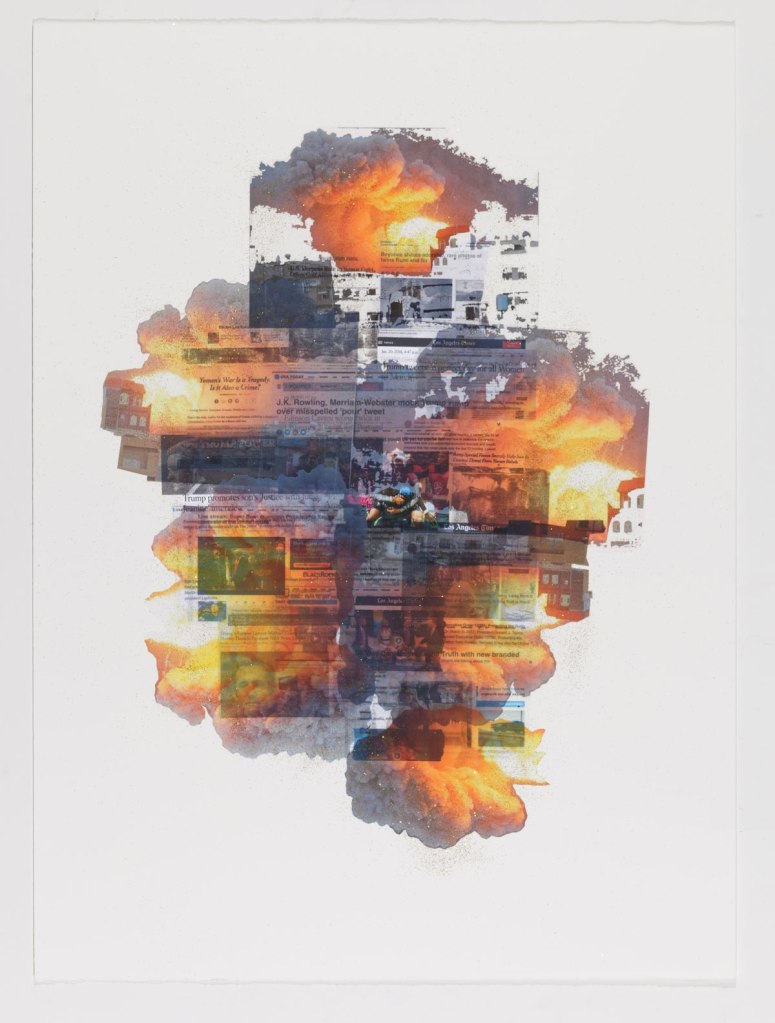

There are also more overtly political collages such as The day after (2018). Could you talk about that?

‘The day after’ emulates the front page of a newspaper. Stylistically, I was pulling from The New York Times and the Los Angeles Times. It references the day after a Saudi airstrike landed in a very busy district in Yemen and struck a school bus carrying a group of kids on a field trip. At least 40 children died, and over 50 people in total were killed. It did make some headlines but not as many as it would have had it happened elsewhere. In the U.S., the news coverage is really not proportionate to our involvement in foreign conflict. Yemen has been engaged in a war now for six years, and the US has been involved by supporting Saudi Arabia. This is huge because if we pulled out, it would have a drastic effect on the war. We are the number one supplier of arms in the world, in particular to Saudi Arabia. The bomb that landed on those kids was American-made but so many people don’t know this. There is a disconnect between our involvement and our knowledge of this war.

I created this work on invitation to a show of all Yemeni artists reflecting on the war. At first, I struggled with my own identity and responsibility– born, raised, and living in the U.S., I had visited Yemen once but have never lived there. Who am I to talk about this? I felt most obligated to bring attention to our (i.e., the U.S.) role in the conflict. Most of the work I created is a critique of U.S. media coverage of the war. I’ve barely scratched the surface as there are a lot of questions we should be asking. What makes headline news? What takes priority? Who is making those decisions and why? Instead of being informed of the most vital issues, much of our news consumption is clickbait-driven.

You can find out more about Yasmine’s work through her Instagram page and website, links below

https://www.instagram.com/yasmine.diaz/